|

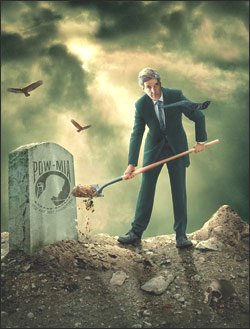

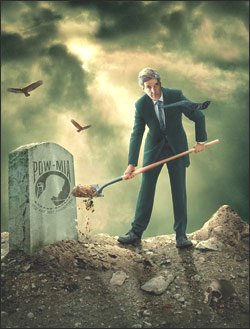

FRANCES A. ZWENIG - NORMALIZE TRADE AT ANY COST! |

Zwenig, in the meantime, was working as principle author of the Select Committee Final Report.Zwenig edited the Final Report read there is "no conclusive evidence" proving United States prisoners of war still remain alive in Vietnam. In an April 4, 2004 Union Leader article, Zwenig described her 'work' on the Committee as "... one of the most worthwhile things any of us have ever done."

Zwenig had opened the door for normalized trade relations with Vietnam and a new career for herself. Zwenig now has a six-figure position as Vice President on the U.S./Vietnam Trade Council, a front organization established in the U.S., which works closely with Vietnam's Communist Party State Committee for Investment. The Trade Council is funded by conglomerates such as Lippo, which lobbies furiously against any U.S. laws perceived as hindering investment in Vietnam's cheap oil and slave labor market.

Frances Zwenig as the Senior Director at the US ASEAN Business Council is also responsible for implementing trade for the ASEAN countries on the mainland, including Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia and Myanmar(Burma). The following articles show her connections with these countries and what she has done to implement trade with the US.

Vietnam: US Firms Seek SE Asian Market

By Martin Crutsinger

Associated Press

November 14, 2000

WASHINGTON -- American business is hungry for a share of the Vietnam market, seeking meet its demand for soft drinks, consumer products and high-tech telecommunications services and gain a foothold in the massive rebuilding of a country heavily damaged by U.S. warplanes a quarter-century ago.

More than 50 U.S. corporations are sending executives Vietnam during President Clinton's three-day visit. The list reads like a who's who of multinational concerns including Boeing, Citigroup, Coca-Cola, General Electric, General Motors, Cisco Systems, Nike and Proctor & Gamble.

The companies either already have operations in Vietnam or want get involved in a country they see as a vast untapped market of 78 million people, about the size of the population of Germany.

''This trip looks [] the future as part of building a lasting relationship with an important country with vast potential,'' said Lionel Johnson, an executive of Citigroup. The giant banking corporation wants expand its foothold in Vietnam -- two branch banks limited offering services foreign companies in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City.

The business leaders, who are paying their own way, will hear from Clinton and other Cabinet officials during a business forum scheduled for Ho Chi Minh City. The president also plans tour a container loading facility emphasize the potential for trade between the two nations if Congress next year approves the trade deal his administration signed with Vietnam in July.

That agreement will grant Vietnam the same low U.S. tariffs enjoyed by virtually all other nations, although Vietnam's trade privileges will be subject annual review by Congress. That was the same status China had for the past two decades before Congress this year granted it permanent normal trade relations.

The normal trade tariffs average around 3 percent, a sharp reduction from the 40 percent average border duty Vietnamese goods now face.

In exchange for access the world's largest market, Vietnam agreed sharply lower its trade barriers American goods, including cutting tariffs on a large number of farm products and manufactured goods, easing current barriers that keep U.S. banks and telecommunications firms out of the country and providing increased protection for U.S. investment and intellectual property rights.

It took a full year after negotiators had reached an agreement in principle get the trade deal signed. Economic reformers in Hanoi had overcome stiff resistance from communist hard-liners who wanted protect the country's inefficient state-run companies.

Just as in China, the administration is hoping a U.S. policy of economic engagement will allow free-market capitalism and democracy take hold.

But even the strongest boosters of increased economic ties with Vietnam concede that U.S. companies have faced numerous obstacles in the six years since Clinton lifted the U.S. trade embargo.

Frances Zwenig, a senior director at the US-ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) Business Council, said Vietnam's decision sign the trade deal showed that ''they want join the global economy. ... Now businesses are willing look at Vietnam again.''

Through July, U.S. imports from Vietnam totaled $448 million, a gain of nearly 60 percent from the same period a year ago, while U.S. exports Vietnam totaled $223 million, also up by nearly 60 percent.

Major U.S. exports Vietnam are industrial and office machinery, fertilizer, leather and other parts for shoes and telecommunications equipment.

Among the leading imports from Vietnam are coffee, fish and crude oil. But once the tariffs are lowered, the World Bank predicts that Vietnamese clothing shipments the United States could jump 10-fold in just the first year.

It is that forecast that has U.S. labor unions worried, believing that the real reason American companies are interested in closer economic ties with Vietnam is tap into that nation's low-wage work force export back the United States.

Nike, the U.S. shoe manufacturer, already produces around 10 percent of its total world output in Vietnam. Those shoes end up mainly in Europe because of the high U.S. tariffs.

Thea Lee, a trade economist with the AFL-CIO, which opposed permanent normal trade relations with China, said unions will fight the Vietnam deal because it does not include safeguards for worker rights and the environment. However, the agreement should face less trouble in Congress than the China deal because the Vietnamese economy is much smaller [The AFL-CIO has recently endorsed Kerry for president].

Analysts caution that businesses should not get carried away in their expectations, at least for the immediate future.

''American companies want get on the ground floor so they don't lose out competitors, but Vietnam still has a way go economically,'' said Franklin Vargo, vice president for trade at the National Association of Manufacturers.

Burma's Image Problem Is a Moneymaker for U.S. Lobbyists

R. Jeffrey Smith

Washington Post Staff Writer

February 24, 1998

The military rulers of Burma are well aware they have an image problem in Washington. The Clinton administration and human rights groups regularly recount how the generals took office by hijacking a 1990 election, keep hundreds of opponents in inhumane prisons and solicit investments from Asian drug lords.

But a bad image can mean big business for Washington's public relations and lobbying firms. Several firms have been conducting a campaign on Burma's behalf in classic Washington style -- producing upbeat newsletters, arranging seminars and interviews and funding all-expense-paid trips -- partly to persuade the Clinton administration to lift trade sanctions against the regime.

For a fee of nearly a half-million dollars, for example, a Burmese company that U.S. officials say is close to the military leadership last year hired a former assistant secretary of state for narcotics control, Ann Wrobleski, and her lobbying firm, Jefferson Waterman International, to communicate the company's "positions and interests," according to the contract. Wrobleski is well known to the regime from her counter-narcotics work, which occurred when Burma was becoming the principal exporter of heroin sold on U.S. streets.

Another, well-connected firm in Burma's capital of Rangoon hired a public relations firm and a lobbying firm last year, paying $252,000 to former television reporter Jackson Bain to help the Burmese Embassy burnish the country's reputation, and an undisclosed sum to the Atlantic Group, a lobbying and public relations company that is working more directly to help overturn the U.S. sanctions.

In addition, various U.S. corporations that want to do business with Burma or already invest there, including the California-based energy company, Unocal Corp., have been spending money to promote the idea that Washington's barriers to new U.S. trade with Burma do not reflect a politically sound U.S. strategy. The sanctions, which President Clinton imposed last May, bar new investment by U.S. firms in commercial or energy projects.

An educational and advocacy organization here called The International Center drew on donations from such corporations to help fund a trip in October by three former high-ranking Defense Department and State Department officials, who met with top military officials as well as with noted opposition figure Aung San Suu Kyi, the winner of the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize for her anti-regime activities.

The three former officials, Morton I. Abramowitz, Richard L. Armitage and Michael H. Armacost, subsequently sent their policy advice to national security adviser Samuel R. "Sandy" Berger and briefed lawmakers and staff on Capitol Hill.

In a private letter to Berger, the three men counseled that some sanctions should remain in place, but urged that Washington try to adopt a more flexible approach permitting international loans for health care and education. Eventually, they added, Washington should reconsider keeping any unilateral sanctions on Burma. "Sanctions over time will become a wasting asset and slow Burma's exposure to the outside world," they wrote.

The administration has given no hint that it plans to relax Burma sanctions.

Unocal, which has a 28 percent stake in a billion-dollar natural gas project in Burma, gave $50,000 to The International Center last July, after hearing from Frances Zwenig, the center's director, about the trip proposal in March. But Zwenig said the funds were not intermingled with those of the other corporations that helped underwrite the trip.

Unocal also donated funds last year to Georgetown University's School of Foreign Service to help fund a Capitol Hill seminar series on Asian nations that is to include a presentation this spring on Myanmar, the name assigned to the country by the junta. James C. Clad, a research professor at the school, declined to say how much the company gave. Corporations "pay but they also get the full spectrum of people" with different views at the seminars, he said.

Maureen Aung-Thwin, who directs the Soros foundation's Open Society Institute Burma project, complained that the reception Burma gets from such institutions in Washington "sends really mixed signals to a government that is beginning to feel the pressure of the isolation and the sanctions."

Lobbyists promoting a positive image of Burma say that they are doing nothing wrong. Bain said he knows the Burmese government is repressive and "not ready for prime time." But he said he enjoys the challenge of trying to disseminate information that gives a fuller picture of the country.

The work is an uphill battle. According to the State Department's most recent public report on Burma, covering the six-month period ending last September, the Burmese regime "made no progress" in moving toward democratization and continued its "severe violations" of human rights. "Money from the illicit trafficking of narcotics likely accounts for a substantial net inflow" of the nation's foreign currency receipts, the U.S. report said. Hundreds of political prisoners were still subject to "deplorable" conditions, while universities remained shuttered for a second year to help stifle popular dissent.

U.S. officials say they have no evidence that either of the two principal Burmese firms that fund lobbying here is implicated in narcotics-related activities.

Jefferson Waterman International signed a contract in February to provide "various professional, strategic counsel and public relations services to" a company in Rangoon called Myanmar Resource Development Ltd., including arranging meetings with U.S. and congressional officials, according to a foreign-agent registration statement filed with the Justice Department by Wrobleski, the firm's president. The fee is $400,000 plus as much as $100,000 in annual expenses.

The filing describes Myanmar Resource Development Ltd. as a privately owned company that invests in Burma. But several U.S. officials said they believe it is either closely connected with the military regime or an arm of its leadership, and internal State Department cables have identified Jefferson Waterman as the "U.S.-based lobbying firm" for the junta itself.

Wrobleski, who worked as a projects director for Nancy Reagan before becoming assistant secretary of state in 1986, was instrumental in denying Burma U.S. anti-narcotics aid following social unrest there in 1989. She said then that Burma was unlikely to make progress in countering narcotics "until a government enjoying greater credibility and support among the Burmese people than the current military regime is seated in Rangoon."

That regime remains in place, but Wrobleski's firm recently expressed a more upbeat viewpoint, advertising Burma in one of its periodic Myanmar Monitor newsletters as a "beautiful and exotic country . . . [that] offers much to tourists, photographers, scuba divers, historians and others." Another newsletter published by the firm repeated the junta's claim that the United States had engaged in terrorism by helping fund the work of a dissident group outside the country.

Asked for comment, Wrobleski refused to answer any questions about her firm's work, saying "we don't discuss what we do for our clients" or any related issues.

Bain, a former White House correspondent for NBC News and anchorman for WRC-TV, runs his Alexandria-based consulting firm, Bain and Associates, with his wife Sandy Bain, a former free-lance contributor to The Washington Post.

Their filing with the Justice Department states that they earn a monthly fee of $21,000 from Zay Ka Bar Company Ltd. of Rangoon, a private, 50-employee firm involved in the construction and development of hotels and other real estate. But U.S. officials say they believe the Burmese company is engaged in business deals with members of the country's leadership, and Bain says this may be true.

A series of internal documents from Bain's firm, which was provided to The Post by sources who asked not to be named, provides a window into how Washington public relations firms conduct a campaign on behalf of an unpopular client.

The memos outline an ambitious plan, for example, to improve the country's image through a series of "defensive and pro-active" measures, including booking speeches by sympathetic businessmen and journalists, arranging luncheon briefings with embassy personnel, "coordination of key messages" with U.S. companies seeking deals in Burma, and "placement of stories through reporter/editor contact."

Bain said in his Sept. 3 Justice Department filing that his client was not a part of the government. But his firm has repeatedly sent its advice directly to the Burmese ambassador in Washington, Tin Winn, or his deputy, Thaung Tun, according to the documents. Progress reports on its work were sent directly to Lt. Col. Hla Min, director of the defense ministry's office of strategic studies and the regime's chief publicist.

On Nov. 12, according to one memo, Bain complained to Thaung Tun that "the last invoice for expenses and November retainer has not been paid," totaling $31,723. He said in an interview that this was merely an effort to enlist the embassy's assistance in putting pressure on Zay Ka Bar.

Last July was a particularly challenging month for Burma's backers after Secretary of State Madeleine K. Albright, attending a meeting of Asian nations, called Burma the only nation in the group that had refused to honor election results, and had banned fax machines, had closed universities, and "protects and profits from the drug trade." Zwenig was Chief of Staff to former UN Ambassador Albright.

Bain bounced back in August with a promise that "we are actively cultivating" reporters and editors, and told his client in September that what the country needed was some "positive, media-quality photos."

In October, he reported that "we are working on scheduling editorial board meetings with the Washington Post and the Washington Times. We have hand-selected our targets at these papers and have begun efforts to arrange meetings for Amb. Rabb and Minister Thaung Tun."

The reference was to Maxwell Rabb, President Ronald Reagan's ambassador to Italy, who said in an interview that after visiting Burma last year, he concluded the country is getting a "bum rap." Rabb's daughter, Priscilla Ayres, is married to Larry Ayres, the head of the Atlantic Group and a lobbyist for Zay Ka Bar.

A meeting was arranged at the Washington Times that resulted in a story that quoted the Burmese ambassador saying the country had waged a successful fight against drugs and encouraged a multiparty system. No meeting occurred at The Post.

In an effort to suggest that Burma is taking its anti-drug responsibilities more seriously than Washington alleges, for example, Jefferson Waterman is offering an all-expenses-paid trip to Burma next month for U.S. journalists "to hear the government's side," according to an official of the firm. Bain is paying for a similar trip for U.S. and foreign journalists this week.

Frances Zwenig, who organized the earlier trip to Burma by three former senior U.S. officials, is a former staff member for Sen. John F. Kerry (D-Mass.) who now runs the Burma/Myanmar Forum for The International Group. In a letter to the president of Unocal last March, she promoted the idea of "bringing a high-level group" to the country, according to a copy of her letter.

The credentials of the group she assembled are indeed impressive. Abramowitz was ambassador to Thailand from 1978 to 1983 and Turkey from 1989 to 1991 and president of the Carnegie Endowment for Peace from 1991 to 1997. Armacost was ambassador to the Philippines from 1982 to 1984 and Japan from 1988 to 1993. Armitage was assistant secretary of defense in the mid-1980s. Zwenig said she wrote to "lots of corporations" to obtain funding for the trip, including some that do business with Burma now and some that simply oppose any U.S. sanctions -- but she declined to name them. In a July 29 letter to the Washington-based director of the Boeing Corp.'s commercial aircraft division, Zwenig noted for example that "a lot is demanded just now of those who are concerned about the U.S.-Myanmar relationship" and said she hoped "we will be able to work together" to fund the estimated $75,000 cost of the trip.

Boeing, which hopes to gain the right to sell aircraft to the Burmese government, subsequently contributed $5,000 toward the trip, according to Maria Sheehan, a spokeswoman for the company. She added that Boeing has also contributed funds to underwrite lobbying by a consortium of companies, known as USA-Engage, that was formed to fight state laws barring investments in Burma and promote the withdrawal of various federal trade sanctions.

Zwenig, on Sept. 19, sent a draft schedule for the trip to Tun, at the embassy, saying "I would like you all to review it and help me edit it," according to a copy of her letter.

Asked at a Nov. 5 briefing for congressional staff members if they had any reservations about having embarked on a trip funded by commercial investors in Burma, Armitage said he would have reservations "had we been working for any investors" but added, "I don't know that we knew who was paying for the trip." Abramowitz said "we went without any agenda" on a trip that was funded by The International Center. "We didn't go to work for anybody and I find the question offensive," Abramowitz added.

Free Trade Agreement -- Thais Punt on Trade Talks

By Shawn W. Crispin in Bangkok and Murray Hiebert in Washington

Far Eastern Economic Review

4 March 2004

THE UNITED STATES and Thailand are set start negotiations in June toward forging a free-trade agreement (FTA), a deal that could lower trade barriers across a wide range of industries in both countries. At the same time, there are signs that the talks could be hampered by politics, with the perceived loss of American jobs developing countries becoming a hot issue in the run-up November's U.S. presidential election.

Preliminary studies suggest the FTA would be a win for both sides, though it would have a much bigger impact on the Thai economy because of its smaller size. An impact assessment recently completed by the Thailand Development Research Institute (TDRI) and the American Chamber of Commerce predicts that lowering tariffs and non-tariff barriers under a bilateral FTA would increase Thai exports the U.S. by 3.4% and boost total GDP by up 1.3% per year.

That could be good news for many of Thailand's exporters, which currently ship around 20% of their products the U.S., but which in recent years have lost market share cheaper Chinese and Mexican producers. A U.S.-Thai deal that promised better protection of foreign investment might also help boost flagging U.S. capital flows into Thailand, which in 2002 were a net negative for the first time in more than 30 years, according Bank of Thailand balance-of-payment statistics.

Ever since World Trade Organization-led multilateral trade talks collapsed last year in Cancun, Mexico, much of Asia has been opting for the bilateral track forward their trade-liberalization agendas. Major Asian traders such as Japan, China and South Korea are all in the process of negotiating big bilateral deals with neighboring countries. However, there are growing signs that the bilateral track could stumble for the same reason that multilateral talks collapsed: entrenched resistance freeing up agriculture markets.

The U.S. and Australia nearly walked away from their bilateral pact in early February due to disagreements concerning U.S. protection of its sugar, beef and dairy industries. Meanwhile, Japan agreed last year to bilateral trade talks with Thailand on condition that Bangkok would not push for access to Tokyo's tightly guarded rice market. For the U.S. and Thailand -- two of the world's biggest food exporters -- contentious agriculture issues will be prominent during negotiations.

"We will want more access [Thailand's] agriculture markets," says a Bangkok-based U.S. diplomat charged with economic affairs. "We want rules that will make trade more transparent and fair to our traders." A senior Thai official, while noting that both sides have sensitive areas, agrees that "agriculture will be among the most difficult . . . The farming sector in both countries is very political."

Thailand levies a 23.6% average tariff on the agricultural products it imports, compared the U.S.'s 7.1% import tax, according the report by the TDRI and the American Chamber of Commerce. However, the U.S. uses a complicated mix of quotas, subsidies and strict food-safety requirements hamper agricultural imports, providing a cushion for some farming sectors like sugar and rice, TDRI researchers note. Both countries have powerful farm lobbies that prefer protectionism export-promoting policies.

That means there is strong domestic resistance the deal on both sides. Aside from the current anti-dumping case that the U.S. has taken up against Thai shrimp producers, Washington and Bangkok have had rocky trade relations in recent years, particularly over agriculture and pharmaceuticals. Thai Commerce Ministry officials lodged a protest with the U.S. Trade Representative's Office and threatened retaliatory measures when an American entrepreneur attempted patent Thai jasmine rice in the U.S. in 2002. The case was resolved before going too far.

The U.S. was also forced to scrap a proposed debt-forgiveness-for-reforestation deal in 2002 due to Thai suspicions that big American pharmaceutical companies might use the agreement as a way to patent genetic materials found in Thai forests. Now there are fresh concerns among some Thai agriculture and environmental groups that Washington will push for greater market access for the genetically modified foods and seeds that big U.S. agribusinesses produce, but which critics contend have unproven food and environmental safety records.

The two sides also teetered on the edge of a full-blown trade war in 2001 when the Thai government produced generic HIV-Aids drug treatments under a compulsory licensing arrangement. The U.S. threatened levy high tariffs on various Thai export items, but relented when the WTO ruled in favor of compulsory licensing of HIV-Aids medicines for some developing countries. Trade analysts, meanwhile, note that last year's U.S.-Singapore trade pact -- which will likely be used as a blueprint for a U.S.-Thai FTA -- includes provisions transcending normal trade pacts. In particular, American negotiators are expected to push for intellectual-property and patent-protection laws up and beyond WTO needs, stronger enforcement of competition laws, and the establishment of a third-party dispute-resolution mechanism that would bypass the Thai judiciary.

"There will be a lot of hurdles," says Frances Zwenig of the U.S.-ASEAN Business Council. "The Thais can learn from the successes and failures" of other recent American FTAs, she adds. However, advisers to the Thai government are already lobbying for a 10-year cushion implement the intellectual-property-protection measures Singapore agreed . Meanwhile, Thai negotiators are gearing up beat back probable U.S. demands for stronger patent protection for pharmaceuticals, say Thai officials.

"U.S. drug companies could ask for too much. That could spoil the deal," predicts Somkiat Tangkitvanich, a researcher at TDRI. "If we offer the U.S. too much, we'll have do the same with all the other countries we are negotiating FTAs with." These include China, Japan and Australia.

Despite the hurdles, Thai Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra has stated his aim is hammer out a deal by the end of this year, due concerns that a Democratic Party victory in the U.S. presidential election will usher in an era of protectionism. Some Democratic Party candidates are making protection of U.S. jobs from foreign competition a campaign plank. But U.S. officials say it will take one or two years broker and ratify an agreement.

Some Thai trade groups and opposition politicians complain that any rush seal a deal could mean Thai negotiators failing to take on board concerns raised by small-scale businesses and farmers about the impact of an FTA on their livelihoods. "We should know when say 'no' on issues we simply can't say 'yes' ," says Kiat Sitheeamorn, chairman of Thailand's International Chamber of Commerce. "If [the government] pushes too fast, it could cause a backlash."