By John Corry

Published 3/9/2004

|

AWOL on MIAs By John Corry Published 3/9/2004 |

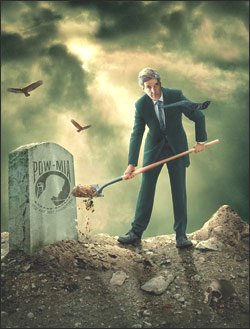

And that, I am sure, was what so upset Kerry. Perhaps he even felt guilty. The article had also raised the possibility -- in fact, I thought it a very strong possibility -- that there were still American prisoners in Vietnam. But I don't think Kerry wanted to know about that. He was an authentic Vietnam War hero, but he was also part of the MIA cover-up.

For the year before the article appeared, the Senate Select Committee on POW/MIA Affairs, with Kerry as chairman, had callously sidestepped the MIA issue. "There is no proof that U.S. POWs survived," the committee said in its final report, "but neither is there proof that all of those who did not return had died."

This was moral cowardice of a high order. After more than a year and a half of hearings, the committee would neither confirm nor deny that servicemen had been left behind to die. Buried in its 1,123-page final report, though, and in thousands more pages of unpublished depositions, were pieces of information that could hardly be ignored.

SATELLITE IMAGERY, FOR example, had picked up the distress signals, and even the names, of downed American pilots on the ground. And the distress signals -- combinations of letters and numbers -- appear in photographs taken after, not before, March 1973, when North Vietnam released 591 Americans in Operation Homecoming. President Nixon told the nation then, "All of our American POWs are on their way home."

But they weren't, of course, and that should have been apparent. As far as I know, for example, the 591 returnees included no amputees or burn cases; there was no one maimed, disfigured, or blind. The most afflicted POWs, I suspect, had either remained in Vietnam, or been murdered.

More tellingly, Nixon had sent a secret letter to North Vietnam Premier Pham Van Dong two months before Operation Homecoming; it reflected an unpublicized understanding reached by Henry Kissinger and Le Doc Tho, a member of the Hanoi Politburo, when they signed the Paris Peace Accord on January 23, 1973.

Nixon told Pham that the U.S. would "contribute to postwar reconstruction in North Vietnam," in an amount that would "fall in the range of $3.25 billion of grant aid over five years...other forms of aid...could fall in the range of $1 to 1.5 billion."

None of the aid was extended, however, although if it had been North Vietnam might have returned all its captives. A 1969 study by the Rand Corporation had said it was doubtful the POWs would be freed immediately after a peace agreement was reached. It was "more likely," the Rand study found, that North Vietnam would await "concrete evidence of U.S. concessions before releasing the majority of American prisoners."

But no concessions were forthcoming, and there was no possibility they ever would be. Nixon would soon be undone by Watergate, and Congress wanted no more of the war. True, Nixon had said the POWs were on their way home, but he also had said:

SO BACK NOW TO THE 1994 American Spectator article that so annoyed John Kerry. I have been a journalist for some four decades, and it involved the most painstaking and difficult reporting I have ever done. The MIA question was shrouded in rumor and misinformation. Much of it had been dispensed by the merely gullible or misinformed, but much of it had also been dispensed by frauds and charlatans. One had to work hard to separate fact from fiction.

I cannot claim now to have written the complete story on MIAs, but I am quite sure I did a responsible piece of reporting. And while the Spectator article cannot be easily summarized, I offer the following as a sample of what it found.

As chairman of the Senate select committee, Kerry might have given us the definitive answer on this and other MIA matters, but I think he had another agenda. Perhaps he thought it more important. Along with so many other liberal thinkers and policy-makers, he wanted to normalize relations with Vietnam. But the MIA issue worked against this, of course, and I think Kerry just wanted it to go away.

Meanwhile it would be pleasant to report now that the Spectator article, while angering Kerry, also galvanized conservatives and roused them into making amends for the wrong that had been done to our missing men. But no other conservative publication took up the cause, and as far as I know, no conservative talk-show host showed any interest; and neither did any of the Washington tough guys who spent the Vietnam years in graduate school, but carry on so bravely now about committing Americans soldiers to dangerous places.

It is unlikely that the MIA question will ever be an election issue, although I wish it would be. We broke faith with men who fought for their country, and we ought now to admit it.

John Corry is a senior editor of The American Spectator.